Broadcasting House

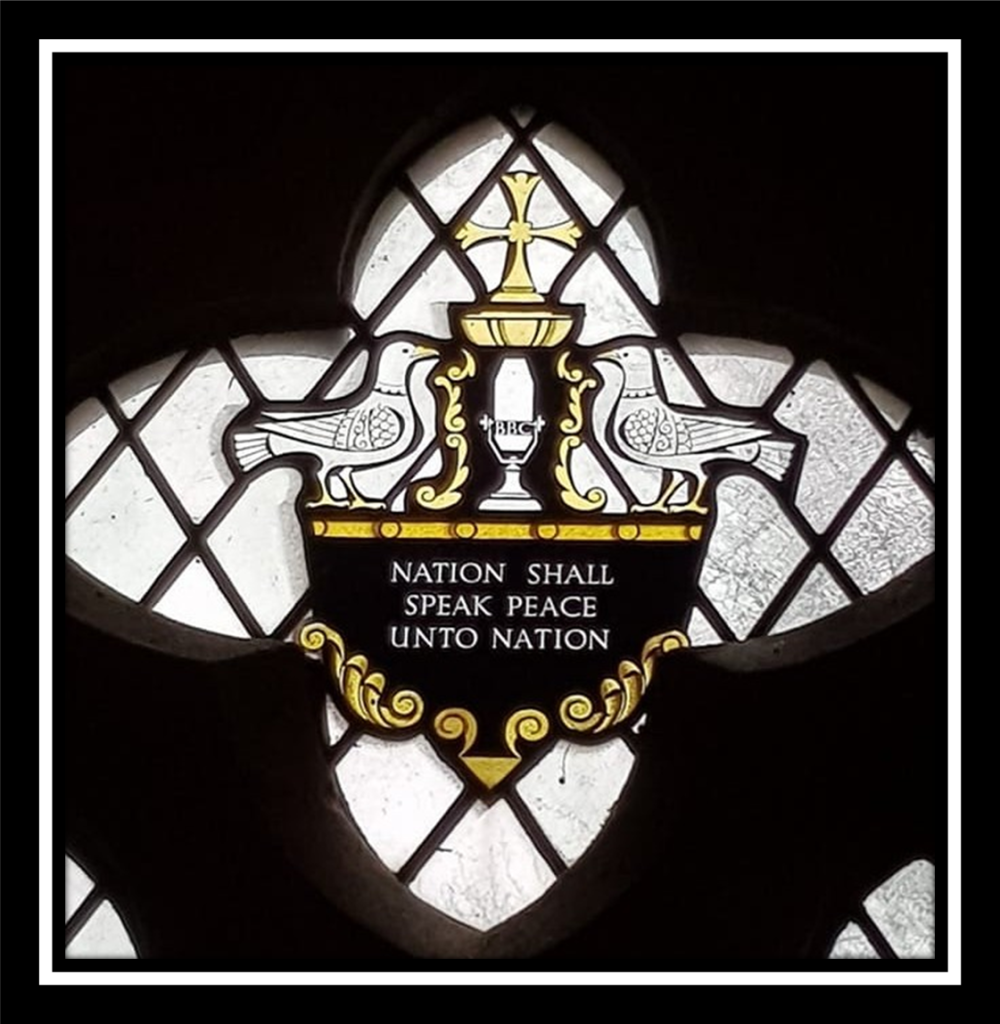

Back in the day, I worked at BBC Broadcasting House on a few occasions (recording radio shows for RTE Ireland). I once smiled at John Peel in the lobby there, and witnessed John Humphrys dashing out of the building, but this was as near to celeb stalking that I could manage. There was a buzz about the place and a sense of weight to what went on there. This was before the building had its revamp, so it still held that mid-20th century feel of being at the heart of national conversation, its 1920s architecture a reminder of aspirations after The Great War: “Nation shall speak peace unto nation”, was inscribed above the entrance (and indeed celebrated in stained glass in All Saints’ church in Thorp Arch!). This was a vision rooted in, and quoting Scripture, 2750+ year old words from the prophet Micah.

Micah’s challenge

When he wrote this, the prophet Micah was addressing Israel and Judah (his own people) in a time of turmoil. This was the middle of the 8th century B.C.E. The Assyrian Empire is devastating the region, defeating Samaria and then Israel itself, leaving the southern kingdom of Judah alone to carry the flag of the people of God. Their calling was supposed to be acting as a godly light to all nations. But this must have looked like an impossible task. Devastation lay all around them. Refugees fleeing Assyrian persecution must surely have sought comfort and refuge among the people of God in those times. Perhaps there were people among them who spoke of these refugees as an invasion, framing them as a threat to the life of the nation using rhetoric redolent to our 21st Century ears of 1930s Germany? This would have been a time of isolation for these nations, lying apart from the major empires, political groupings and trading blocs. And Micah addresses a familiar human problem: in challenging times, at a time of national uncertainty and turmoil, how do we hold our nerve as people of faith and not nod along with those who call us to behave selfishly, unjustly and badly? How do we challenge those who seek security by scapegoating the vulnerable and minorities? How do we stand against those who stoke fear, who turn us against one another? And how do we offer sufficient space and grace to those whom we challenge so they can change direction (aka repent), change their tone, and bravely join the cause of righteousness?

On earth as it is in heaven?

Micah’s prophecy had two key themes. First, he challenges Israel and Judah to be more godly in their behaviour: they need to address their own evil behaviour rather than simply focusing on their enemies. Second, they need a vision of God’s eternal kingdom, beyond their current, challenging circumstances. Much of Micah’s indictment against Israel and Judah involves these nations’ injustice toward the powerless. Micah singles out corruption, robbery, mistreatment of the most vulnerable, and a government that lived in luxury off the hard work of its nation’s people. So what can we learn and apply from Micah today, here in the UK?

The BBC and me

Growing up in the UK in the 1970s & 80s, it was BBC radio that I tuned into in my bedroom. I had a portable radio with a mono earpiece and would often stay up late expanding my musical horizons on late night Radio 3, or listening to the world service and learning about life in these far-off places whose daily life and differing perspectives were so very different to my own. BBC Radio expanded my horizons and somehow informed my growing faith at the same time.

The music of Philip Glass blew me away in 1976 when I first heard “Spaceship” from his brand new opera Einstein on the Beach late one night. Glenn Gould’s Marmite approach to Bach, quirky and very personal, inspired me to start composing myself. Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” was an unexpected thing of beauty. The keyboard sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti made me laugh out loud at their reckless exuberance – the rock guitar shreds of their day. The late night programming on Radio 3 was where the Beeb brought out the fun stuff back then.

When I moved the dial to find the BBC World Service, this meant that I became aware of the wider world. I remember being fascinated by the challenges facing South American and African countries and Eastern European communist states, and how vulnerable minorities were so often the victims of injustice under regimes of very different political hues. I saw how fascism, communism, apartheid, occupation, dictatorships and political chaos all crushed the powerless: how extreme politics of both right and left each allowed evil to triumph. I also learned how important the arts are worldwide in enabling a wide variety of people to tell their stories and help us all gain understanding and empathy for how everyday life is affected by the huge, impersonal tides of history and politics. As my faith grew alongside all this, I also grew to understand how the prophets, the apostles and Jesus himself have always spoken into everyday life, into culture, into politics.

Part of the challenge of the Christian Faith is to learn how to apply what we know of God’s heavenly kingdom from Scripture here on earth, so having an open mind to learn about the world, as well as properly informed sources of information are part of our equipment as we work out how to pray, speak, engage and act in order to make the world (and ourselves) a better, more holy place.

A less famous inscription can be found outside Broadcasting House. The author George Orwell worked at BH for a time, and beside his statue are words of this committed humanist which sit very well alongside Micah’s:

If liberty means anything at all it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.”

George Orwell – an essay on the freedom of the press, written as a preface to ‘Animal Farm’ but not included in the original publication

These words certainly apply to Micah whose criticism of his nation cannot have made him universally popular, especially among the rich and powerful. Orwell himself commented in the same preface to Animal Farm that he knew well the excuses intelligent people of influence make for not speaking out, but that these usually boiled down to timidity and dishonesty. The people of God are always called to speak out, to overcome their timidity and to be honest when their faith and morality compels them to call out injustice, oppression and evil. In every generation, in every country, we are called to be Micahs in the here and now. Being more Micah means being dismissed as woke, being called a snowflake, being told that Christians should stay out of politics. It means that our speaking up will be equated with “cancelling” the rhetoric and action we oppose. It means “whataboutery” will be used to deflect from the criticisms we raise. It means that we will be attacked as a distraction from the issue we raise – that we and our speaking out (rather than the evil we seek to highlight and argue against) becomes the story. It means all that and more. The same applies to any prophet in any age, and most certainly applied to Jesus. If it doesn’t apply to us Christians, we need to up our game.

Two mottos: one challenge

Let us speak peace unto our own nation, and to all nations. The peace Christians are called to share is the Gospel – God’s Good News for all people. Sharing God’s Good News inevitably involves calling people to look at themselves critically, and then to turn from whatever they find within themselves which is wrong, unworthy, and evil (a process called repenting). In other words, we’re called to tell people what they often do not want to hear, but also to offer space for repentance: to have the grace to let people repent and accept them when they do. We’re also called to reflect and repent ourselves – this isn’t about setting ourselves up as a moral authority, but pointing ourselves and others towards God, the only true source of authority. But as Broadcasting House’s mottos remind us, if we are not truly pursuing peace in the human heart and in the world, if we are not standing up to populist ‘othering’ of groups of people, whether refugees, people of sexual and gender minorities, disabled people or citizens of other nations, and if we are not speaking words of challenge, rebuke and a call to repentance, then it is not liberty we are pursuing. It is something far different, far darker, and far from godly.